Hopper’s story is a simple one. He was born in Nyack, N.Y., attending a local private school followed by the Nyack High School. He was a shy child, nicknamed “Grasshopper,” whose social alienation only increased when he grew to six feet at age twelve. In 1899, he went to a commercial art school, but soon after enrolled in the New York School of Art where he studied for six years. It was there that he was taught by Paul Henri (an American whose name was pronounced Hen-Rye). Henri was the person who influenced Hopper’s art the most – particularly in the area of realism. Hopper twice traveled to Europe to study, a rite of passage for young artists, but was not strongly influenced by what he saw. Nor did he follow the “wild” behavior of other youthful artists in Paris. (One of the people with whom Hopper stayed wrote to his parents, describing the young artist as a “Mama’s boy”).

Hopper returned to New York City where, in a love-hate relationship with commercial art (he was good at it, but hated doing it), he earned a living, painting for himself on his days off. In 1913, he moved into a somewhat bleak top floor apartment at 3 Washington Square which had 74 steps, no elevator and a communal washroom that was shared with other residents on the floor. Although Hopper would earn well from his paintings, he only moved once – to another apartment on the same floor. When he got married in 1924 at age 42 to artist Josephine Verstille Nivison (who was one year younger than him), the couple continued to live in the apartment, though they did spend their summers in Cape Cod.

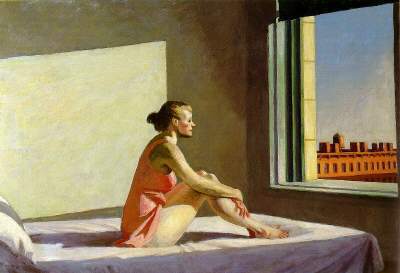

Morning Sun by Edward Hopper, 1952, is a voyeuristic view of a woman on a bed in front of a window. It is possible that the light from the window was inspired by Hopper’s love of the theater and the dramatic lighting he saw there

Hopper met Jo when they were both students of Paul Henri. She was an actress as well as an artist and in many ways was Hopper’s opposite; she was chatty and gregarious whereas Hopper was introverted and given to long silences. One thing they did share was a love for theater, movies and, of course, art. The couple’s life revolved around Hopper’s career, and Jo arranged the sale of paintings and negotiated their prices. When they married, Jo forbade Hopper from using any female models other than her. From then on, the women in Hopper’s paintings were based on Jo, even if he did change her face, make her younger and give her wider hips.

Hopper was so private he prohibited his sister from speaking to the press about their upbringing. And when interviewers would climb the four flights of steps to his studio apartment, they would find a tightlipped Hopper, with the only objects in the studio being an easel (that was covered for the interview) and a mirror.

It is said that Hopper suffered from depression and that the loneliness of the figures in many of his paintings (even when they were in groups) reflected his own solitude. The subject matter and the style of Edward Hopper were consistent throughout his 60-year-career. What changed was his aptitude, which resulted in hauntingly captivating paintings for which he is considered the greatest American realist of the twentieth century.

Sources:

The Essential Edward Hopper by Justin Sprint. 1998, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York

Edward Hopper by Lloyd Goodrich. 1971, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York

Hopper by Rolf Günter Renner. 1993, Benedikt Taschen Verlag, Cologne